From Beth Parnicza

When we prepare special programs, exhibits, or even blog posts, we often pull soldiers’ letters and diary accounts written immediately following the action. Untainted by the warm glow of nostalgia, such accounts have an authenticity that draws us in as historians.

With so much of our interpretation and research focusing on a battle or its immediate aftermath, we are sometimes guilty of forgetting that these moments are brief touchstones in the lives of soldiers, which, if they were lucky, stretched far beyond the few days that command our attention. One such account that we draw on to the point of canon is Rice Bull’s spectacular recollections of the Battle of Chancellorsville. Bull served with the 123rd New York Volunteer Infantry, and it was both his and his regiment’s first major battle. Bull completed the memoirs of his wartime experience in 1913, fifty years after the Battle of Chancellorsville, but his clarity and descriptive ability speak to a clear mind and a sharp memory of these transformative events.

Rice Bull volunteered with the 123rd New York Infantry in the spring of 1862, explaining, “it was our sense of duty; …if our country was to endure as a way of life as planned by our fathers, it rested with us children to finish the work they had begun.”

After describing a collective effort to overcome the fear of battle, Bull described being wounded as his regiment confronted Confederates attacking in the woods west of Fairview: “I had just fired my gun and was lowering it from my shoulder when I felt a sharp sting in my face as though I had been struck with something that caused no pain. Blood began to flow down my face and neck and I knew that I had been wounded.” As he moved toward the left and rear, “…when back of Company K felt another stinging pain, this time in my left side just above the hip. Everything went black. My knapsack and gun dropped from my hands and I went down in a heap on the ground.”

Bull’s account is particularly remarkable for his account of lying wounded on the field for nine days at a makeshift field hospital near the Fairview house. Beyond the agony of his wounds and the suffering cries of his comrades, Bull noted the weather, which took a turn for the worse a few days after the battle. A thunderstorm, followed by a cold, steady rain, made the unsheltered miserable and caused two men to drown. Bull wrote, “It is now fifty years since that day, but in my memory, I can yet see those wounded men as they lay on the ground half covered with the yellow mud and water.” Decades later, the horrible sights he witnessed were seared into Bull’s memory.

To our knowledge, Bull visited the site of his wounding but once after he was wounded, as the armies were passing north for the Grand Review at the end of the war in 1865. Recalling that visit to the battlefield, Bull wrote that he was glad to see the field two years later, but his thoughts turned quickly to the fallen: “But now what a change! Everything was quiet and peaceful. Almost the only sound, other than our excited words, was the singing of the birds, perhaps a requiem to the dead, who in thousands all around us lay in unmarked and many in unmade graves.”

On this now-peaceful landscape, Rice Bull and his comrades occupied a line in the woods seen in advance of these artillery positions on the morning of May 3, 1863.

Though Bull wrote of peace, he felt anything but peaceful. He later wrote, “I lived over again in my memory the awful eleven days spent there where such suffering was endured. I felt a great sense of gratitude to God that I had…survived my wounds at Chancellorsville…and rejoiced that I was alive and homeward bound.” As Bull and his comrades marched north, they carried the war and its memories and wounds with them, heading to their final parting as a company. Bull wrote of the sadness of parting from his tent-mates, but he also must have felt a tinge of uncertainty at resuming the life he had left behind. “Surely we all rejoiced that the end had come, that victory was ours and that home was near. But there was after all a sadness deep down in our hearts in this parting hour.”

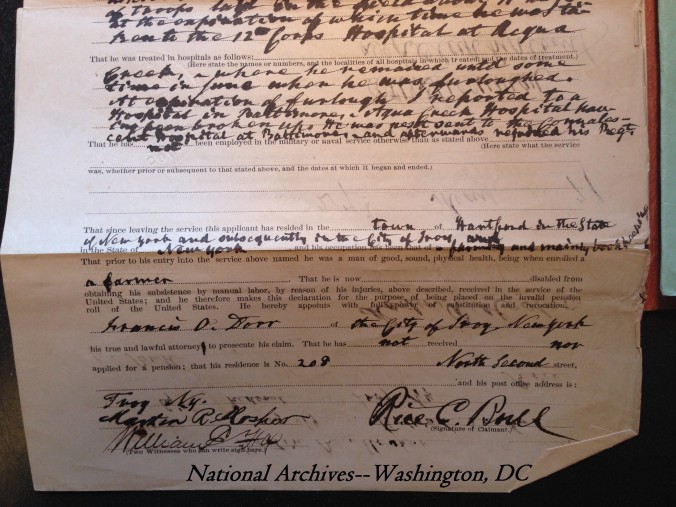

Before the war, Rice Bull had been a farmer, but wounds to the cheek and hip left him unable to continue this pursuit. When he filed for a pension in 1879, his examining physician, Dr. R. B. Bontecou, who had seen his fair share of the effects of war (learn more about Bontecou on the Spotsylvania Civil War Blog here), recorded of Bull’s wounds that, “He has always been more or less lame from it & it interferes with his ability to labor.” In Bontecou’s estimation, Bull was permanently disabled 1/2 from his wound to the side and 1/8 to 1/4 disabled from his wound to the face.

The Examining Surgeon’s Certificate from Rice Bull’s pension file, detailing the two gun shot wounds that Bull received at the Battle of Chancellorsville and their lasting impact.

In light of his wounds, Bull took up banking in Troy, New York at the Mutual National Bank, eventually rising to become its cashier. He later became a founder and secretary-treasurer of the Troy and New England Railroad, as well as the treasurer of the Ninth Presbyterian Church. Bull finally passed away on May 19, 1930, a well-respected member of the community, and his memoirs passed into the hands of his children.

Further documentation in Bull’s pension file shows that by 1879, he had taken up bookkeeping because he could no longer perform his earlier occupation as a farmer.

Reflecting on the end of his service and the transition back to civilian life, Bull expressed the challenge that soldiers confronted in adjusting back to the world they left behind:

“Looking back now [1913] I realize, far more than I did then, how unprepared we were to meet the life conditions that faced us, not alone from wounds or broken health but from the greater reason that our long absence during the years of life when we would have fitted ourselves by education and experience for a successful effort were years gone. Many faced the future with the handicap of physical weakness, ignorance, and lost opportunities.”

Rice Bull, like so many of his comrades, faced the ultimate conundrum of war. War had a profound mental and physical impact on his life, altering his future prospects forever. It had done both immense good and bad on a national and a personal scale. Rice Bull was able to rise to its challenge and shape a life worthy of pride in its aftermath, but his reflections describe the loss of opportunity, life potential, and capability that the war wrought for him and so many of his comrades.

We honor Rice Bull and his comrades, past and present, on this and every Veterans Day.

Beth Parnicza

Sources: Bull’s wartime and postwar experience are drawn from his published memoirs: K. Jack Bauer, ed., Soldiering: The Civil War Diary of Rice C. Bull (Novato: Presidio Press, 1995), 57, 75-76, 245, 249, ix. Rice Bull’s original diary and account is the property of the Rensselaer County Historical Society in Troy, New York. Rice Bull’s pension was pulled at the National Archives.

Thank you Beth. A well told story to celebrate the day.

Well, done. Beth. I enjoyed reading this.

Great sketch. Thanks Beth.

Thanks.

Beth – Great stuff! You didn’t mention you wrote for Mysteries and Conundrums!

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

interesting that he campaigned with the army for 2 more years but was too disabled to farm.