From: Noel Harrison

In early June 1863, Federal troops staged an assault crossing and bridge laying at Franklin’s Crossing on the Rappahannock River, just downstream from Fredericksburg. In later years, the event would often be classified directly or indirectly as a curtain-raiser for Gettysburg, including in 1889 by the publishers of the three-part volume 27 of The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Its “Summary of the Principal Events” listed “June 5-13, 1863. Skirmishes at Franklin’s Crossing (or Deep Run), on the Rappahannock, Va.” as the second of many component-actions of “The Gettysburg Campaign.”

A Gettysburg context makes perfect sense to people who know the future. Union forces indeed abandoned the Franklin’s bridgehead, occupied from June 5 until June 14, 1863, before it could host or become the springboard to a major clash. After Chancellorsville, which had occurred one month before, the next encounter to involve the majority of the units of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia came at Gettysburg in early July. (The opposing mounted forces, with some infantry involvement, fought at Brandy Station on June 9, and a Confederate corps engaged and routed a Union division at and near Winchester on June 13-15.)

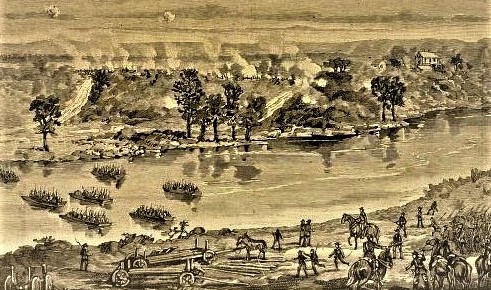

The rarely seen image at left shows the Franklin’s Crossing bridgehead in June 1863 and looks north in a “Confederate’s-eye view” across the site of the June 5 assault by Union forces that had preceded their construction of the two pontoon bridges. Click to enlarge. Source: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. At right is a better-known companion view that looks in the opposite direction. Source: Library of Congress.

(I share the north-looking photograph above in accordance with the New York Public Library’s posted belief that the item is in the public domain under the laws of the United States.)

Yet Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker in June 1863 ordered the operation at Franklin’s Crossing not knowing the future but attempting to predict and influence it. As described in this blog article and its second part, he maintained the bridgehead for more than a week as part of successive plans to move the Army of the Potomac south or southwest to fight in central Virginia, not north or northwest to fight above the Potomac. In August 1862, prior to the Battle of Second Manassas, Union Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter had similarly suggested a Union push from Fredericksburg south “toward Hanover, or with a larger force to strike at Orange Court-House,” to the southwest, as the Army of Northern Virginia itself moved northward.

At Franklin’s Crossing in June 1863, the Rappahannock was passed, and combat did occur, unlike the similarly difficult-to-classify “Mud March” of the previous January. The June fighting waxed dramatic enough to inspire one veteran to reference and (in my read) even elaborate on Stephen Crane’s depictions of battlefield behavior in The Red Badge of Courage, when publishing a recollection of the action in the late 1890’s. Again, a Gettysburg context for the June 1863 events at Franklin’s makes sense to some degree, and I certainly don’t reject it, but I seek companion- or alternate interpretation not grounded in hindsight. My offering of another designation, “Third Fredericksburg,” in the title above emphasizes the perspective of Hooker, whose orders created the bridgehead and formulated an evolving scheme, oriented away from Gettysburg, for the bridgehead’s exploitation. I avoid a parallel discussion of what was known to and planned by his opponent, Gen. Robert E. Lee, other than my use of a pair of quotations from a secondary source, below. I employ “Third Fredericksburg” as shorthand for “Third Battle of Fredericksburg,” a term applied only occasionally to the June fighting at Franklin’s, in biographical sketches of Union veterans in histories of an Illinois county in 1884 and of Dakota Territory in 1915, a Philadelphia newspaper obituary for another veteran in 1910, and the Record of Events published by the editors of the Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the 1990’s.

This map by John Hennessy shows the three-bridge configuration at Franklin’s Crossing at the onset of the Second Fredericksburg operations on April 29, 1863, and provides a good orientation to the modern landscape there. The Union pontoon bridges completed on June 6, 1863—just two, though—were situated in the same general location occupied by the three spans a month before.

I have no more desire to inflate Hooker’s plan into a conceptual masterpiece than I do the resulting, intermittently brisk engagement of June 5-14 around the Franklin’s Crossing bridgehead into anything approaching the intensity of the “Second Fredericksburg” component of the Chancellorsville campaign, in late April and early May, much less that of the First Fredericksburg fighting of December 1862. As I suggest below, Hooker’s motivations for establishing the bridgehead in June 1863 may have included adjusting in the present his military reputation of the future. Yet the story of the events of early June 1863 offers an opportunity—surprisingly neglected thus far in historical writing—to better understand the man who had planned and managed Chancellorsville. Hooker, after all, chose Franklin’s for his opening infantry move in June, just as he had done in late April at the outset of Second Fredericksburg.

On May 7, 1863, one day after Chancellorsville’s close, President Abraham Lincoln was prodding Hooker to resume the offensive. The army commander responded that a thrust was in the works, this time with the operations of all the infantry corps “within my personal supervision.” Hooker supplied an update a week later, informing the president that the service expirations of two-year and nine-month regiments had imposed a schedule adjustment but that his “hope” was to return the army to action the very next day, May 14. Lincoln discouraged the plan after meeting with Hooker in Washington, arguing that the moment of post-Chancellorsville opportunity had passed, with the enemy having had time to repair the communications disrupted during that campaign and also regain the Rappahannock defensive positions that it had “somewhat deranged.”

Within two weeks, Hooker’s own mood swung to caution. On May 28, he ordered Maj. Gen. George Meade to dispatch a Fifth Corps division to replace the Federal cavalry guarding the Rappahannock crossings between Kelly’s Ford and Bank’s Ford. Later that day, Meade assigned the division of Brig. Gen. James Barnes to the task, directing Barnes to “throw up such defenses as will repel any attempt of the enemy to effect a crossing.” Meade in the same orders undertook worst-case planning for a major Confederate piercing of the river line. In that event, Barnes’s soldiers along its eastern segments were to fall back “on the main army” along the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac at and near Falmouth Station, and those along the western segments to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad at Bealeton Station. Meade three days later requested approval to add a division and more cannon to the Rappahannock defenses in the wake of two days of his personal reconnoitering; he found the river fallen to levels that compromised “in numerous places” its protective capacity, and that the dispersal of troops to guard it had so “weakened” Barnes’s division that Meade doubted it could prevent Lee crossing “infantry, cavalry, and artillery” if “he is determined at any sacrifice to force a passage.” After Confederate deserters conveyed rumors of preparations for such a passage on June 4, Hooker on June 3 endorsed Meade’s requested reinforcement, directed him to give special attention to strengthening the defenses at Banks’s Ford, and ordered the Army of the Potomac’s other corps to prepare “for any movement that may be ordered” the next day.

A postwar illustration, looking southwest, of the Union assault crossing at Franklin’s, June 5, 1863. Note the buildings of “The Bend,” Alfred Bernard’s farmstead, at upper right. Source: Samuel Toombs, New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign, p. 23.

A riverine assault and bridgehead at Franklin’s Crossing resulted from a subsequent shift in Hooker’s outlook back toward the bellicose. For Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps, the readiness that Hooker ordered at the end of May and beginning of June, amid concerns about a pending breach of the Federals’ river defenses, became readiness and then an advance, ordered by him at 7 a.m. on June 5, to effect a lodgment in the enemy’s. At Franklin’s Crossing that afternoon and evening, Union troops moved wooden pontoons down a bluff to the river’s edge. Their opponents, the Second Florida Infantry, opened fire and eventually inflicted casualties among all three components of the Army of the Potomac engineer brigade—the 15th and 50th New York Volunteer Engineers and the United States Engineer Battalion—as well as the 77th New York Infantry, who assisted with unloading the pontoons. Capt. Wesley Brainerd of the 50th would later describe how the Floridians’ fire found “[o]ne after another of my men,” who then “dropped down and attempted to crawl away.” Another member of the 50th scrambled back up the bluff with orders for his comrades detailed as oarsmen to descend to the water; he counted near-misses by at least four bullets and quickly adopted a zig-zag course for his climb. The Fifth Vermont and 26th New Jersey infantry regiments arrived as well and tasked some of their number as assault-troops, who with the engineer-oarsmen set off in a small flotilla of of pontoons.

In The Song of the Rappahannock, a memoir published in 1898, Ira Dodd, a Sergeant in the 26th New Jersey in 1863, would recall at least two layers of manned Confederate fortifications confronting the Federals on June 5: a “row of rifle-pits” part way down the slope of the riverside bluff, and, a short distance to the rear, “a little fort.” Union artillery easily suppressed the Southerners sheltering at the latter, in “an inferno of bursting shells and clouds of dust. Woe to the men behind that torn and fire-scorched mound!” Yet the location of the former below the level of the plain, Dodd added, partially or fully shielded the enemy occupants from “the line” of Federal artillery fire. Engineer Capt. Brainerd wrote likewise of Confederates in “a small fort” behind or near an orchard—presumably the trees shown on at least one wartime map at “The Bend,” Alfred Bernard’s estate at the edge of the plain and bordering the river. Although a description of the fighting, penned on June 6, 1863 by Col. Lewis Grant, Dodd’s brigade commander, made no mention of a fort or other detached earthwork to the rear, Grant’s report anticipated Dodd’s future memoir in noting that the outwardly “terrible fire” of the Union artillery actually “had but little effect” upon the rifle-pits.

- Detail from the left-hand/north-looking image at the top of this article. On June 5 the 26th New Jersey followed the road from far-right middleground to descend the bluff to the pontoon-launch area, the eastern end of which is in foreground. Stafford Heights loom in background.

The Confederate defenders turned their attention from the engineers and infantry on the opposite shore to those approaching in pontoons. The 26th New Jersey was attempting its third move over the Rappahannock at Franklin’s Crossing, after such crossings by the regiment during the battles of December 1862 and April-May 1863, and now the first under enemy fire. Ira Dodd would reference The Red Badge of Courage, newly published by the time that he was finishing The Song of the Rappahannock 35 years later, as the entre to describing (italics below) a striking gradation of battlefield behaviors compressed in both time—the late afternoon and early evening of June 5, 1863—and geography—the literal amphitheater formed by the opposing sets of riverside flats and enclosing banks at Franklin’s:

– the terrified casualty, the uninjured coward—In every battle there are a few heroes of the type with which Stephen Crane has made us familiar, whose ingenuity in finding safe places is amusing, and whose antics make life a burden to officers and file-closers. When we reached the [pontoon] boat-landing [on the north bank of the Rappahannock] the ground was absolutely bare; there was not a bush, or tree, or rock; the only possible shelter from the leaden hail was a spring,—a mere mud hole, perhaps three feet in diameter. By lying down and curling himself up in the mud and water a man might fit into it. If the desirability of land is the measure of its value, then that mud hole was priceless, for it was occupied every minute and each occupant was envied by other would-be tenants. As I came down the hill I saw one of these fellows who had just been routed out. A bullet had pierced his arm as he rose from his muddy bed, and he was dancing with pain, clasping his wounded arm with his unhurt hand and muttering angry curses upon the officer who had disturbed his repose. The vacant place was instantly taken by an old gray-bearded fellow from my own company. Over him stood the major, punching the man with his sword, and accentuating each prod with an appropriate remark.

“Come, Peter (a prod), get out of this [prod]; your life is not worth any more than mine!” (final prod). And Peter slowly arose. It makes me laugh now, as it did then, to see his white, scared face gazing agape at the major, the mud and water dripping in festoons from his hair, his beard, and his clothes.

– the momentary coward—When we were half way across the stream a bullet struck the oar of one of our rowers, close to his hand with sharp ping and shock. For an instant the man seemed paralysed; he stopped rowing and our boat’s head swung round, threatening collision with the craft beside us. In that other boat was a red-haired captain, a fiery little Irish gamecock. Quick as thought he grasped the situation, and leaning far over the gunwale with uplifted sword, he hissed at the frightened oarsman:—

“Row, damn you, or I’ll cut your head off!”

Never can I forget the appealing glance of the poor fellow at that impending sword, nor his sudden transformation from helpless inertness to desperate energy.

– the born hero—When we went down to the river that day, Captain [Samuel U.] D[odd]’s company led the line and filled the first boat. The enemy’s fire was at its hottest when they were shoved off. Caring always for others more than for himself, he commanded his men to lie down and shelter themselves, but his perilous duty was to direct the rowers and guide the course of the fleet. He stood up to do it better. The risk was fatal; his commanding figure became the mark for many rifles, and he fell before we were half way across.

– the redeemed hero—In the same boat with the heroic captain was a man from the other regiment who had been a deserter. His conduct in action was to determine his fate. How he managed to get into that first boat I do not know. He must have run far ahead of his own company, but when we neared shore he sprang out where the water was waist deep and, waiting for no one, charged alone up the bank. It looked like sure death; but he escaped unhurt, and I believe was the very first to enter the enemy’s works. Of course he secured his pardon.

Possibly appearing here for the first time in an interpretive venue, this sketch by Harper’s Weekly special artist Alfred R. Waud depicts some of the Confederate defenders of Franklin’s Crossing on the evening of June 5. Library of Congress.

(High-resolution versions of the sketch and catalog information are at the Library of Congress webpage here.)

The assault crossing and capture of the enemy fortifications on June 5 cost the Federals some 63 dead and wounded. Hooker reported a haul of Confederate prisoners of around 50. An officer in the same brigade as the Second Florida put the figure more precisely at 67: two wounded, three killed, and 62 captured.

As with countless other military events large and small, an intermittent war of words, or interpretation, flared from almost the moment of the first shot on June 5 and among the participants on the winning side. In his report Col. Grant, a Vermonter, awarded most of the credit for the bridgehead to the men of his state and located the bulk of the captures of enemies on June 5 not at the riverside fortifications but at the fringe of his expanding picket line “after dark” that day (and under the supervision of Vermonters). Yet around the same time that he penned those words on June 6, a New York Times correspondent dispatched an account awarding the laurels of June 5 mainly to the 26th New Jersey. Elaborating on the Times interpretation 25 years later, in New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign, Samuel Toombs (a veteran of a New Jersey regiment in another Army of the Potomac corps) placed men of the 26th, channeled for their approach to the embarkation sites into “a road cut parallel with the river and fully exposed to the enemy’s fire,” in far greater danger than the Vermonters, whose approach had allowed them to move “rapidly down a narrow gulch” to the river bank while approaching the embarkation sites; “first in the enemy’s works” along the Rappahannock, albeit with a dramatic, neck-and-neck sprint by one of its officers and one of the Fifth Vermont along a road up the bluff; at the lead in making captures even during the bridgehead’s subsequent expansion late in the day—Vermonters to the rear gathered and “turned in” to Grant “all the prisoners taken”—and of course as victims of Grant’s June 6, 1863 report, which Toombs deemed “not the work of a broad or generous disposition.” Capt. Brainerd of the 50th New York critiqued in his diary a sister unit, the Regular Engineer battalion, who “did not stand up to the fight so well that day as did our volunteers.” Rather than blame any of the engineer units of his brigade, however, Brig. Gen. Henry Benham, in a June 11 note to Hooker’s Assistant Adjutant General, complained that Col. Grant’s superior, Brig. Gen. Albion Howe, had not considered “himself as under my directions” and thus declined a request on June 5 to dispatch Grant’s infantry to the river’s edge in conjunction with the arrival of Benham’s engineers. The latter’s June 11 note continued: “The consequence of this was considerable delay, and a long-continued, unnecessary exposure of my men…to the fire of the enemy, by which they sustained very severe loss, much more…than all the rest of the troops…. “

For much of June 5 Hooker had believed that Lee was withdrawing the Army of Northern Virginia from its lines around Fredericksburg with the intention of either interposing his troops between Hooker’s army and Washington or crossing the upper Potomac. The Federal commander at 8:45 a.m. that day ordered the Second, 11th, and 12th Corps to join the Sixth in readiness for movement “at very short notice.” In a telegram sent to Lincoln three hours later, Hooker proposed a crossing-operation at Franklin’s far exceeding his currently modest goal of “a demonstration”: the Army of the Potomac would “pitch into” those Confederates who remained on the south side of the Rappahannock near Fredericksburg and presumably now represented the vulnerable “rear” of Lee’s departing (or side-stepping) forces. Hooker wondered if such a thrust would be in accordance with the indirect option implied in guidelines he had received from Union General-in-Chief Henry Halleck back on January 31. Those urged Hooker to keep in view “always the importance of covering Washington and Harper’s Ferry, either directly or by so operating as to be able to punish any force of the enemy” moving against either place. Around nightfall on June 5, though, Hooker notified the President that he had come to doubt the likelihood of a Confederate withdrawal and now intended to maintain the Franklin’s Crossing bridgehead for only “a few days.” (See Eric Mink’s article here for a fascinating artifact of the Confederate reoccupation of the famous Stone Wall/Sunken Road defensive position during this same period.)

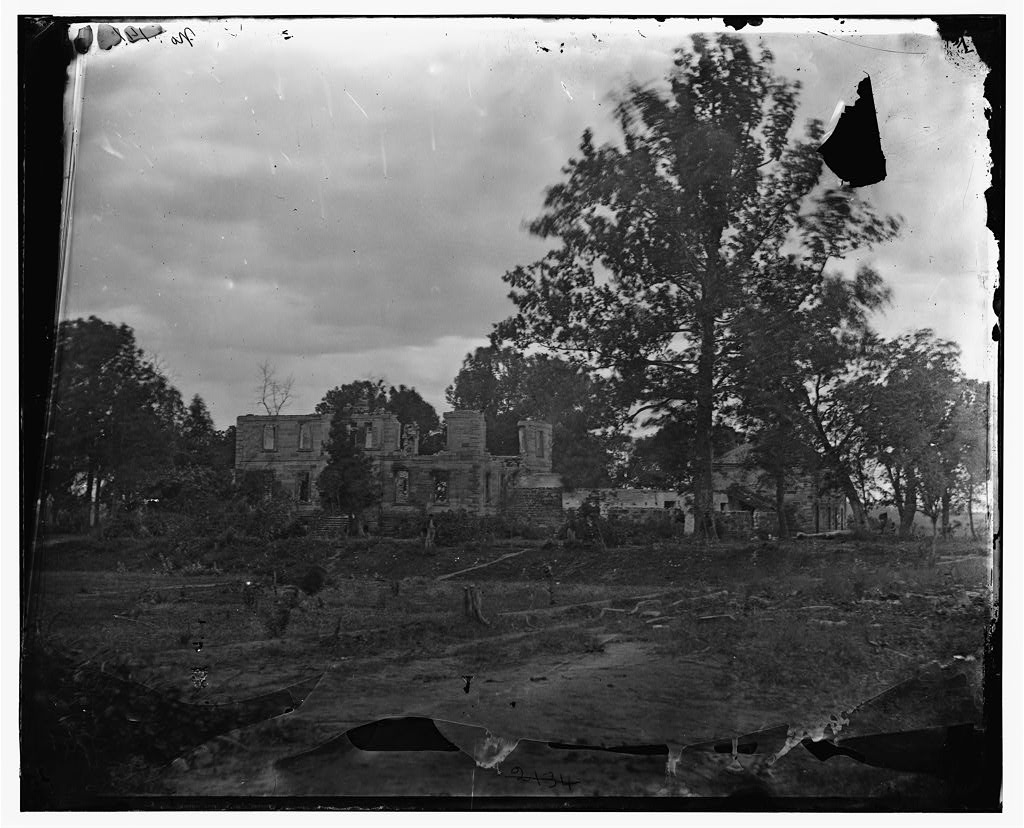

Another rarely seen image: the river side of ruined Mannsfield, looking south from the remnant of its formal garden, during the Federals’ occupation of the Franklin’s Crossing bridgehead in June 1863. My dating of photograph to June is based on historian John Kelley’s leaf-out analysis, summarized in the acknowledgment and endnotes at the end of this article. I suspect that the tree looming over the wall in left background is a leafless exception due to its scorching in the fire that had destroyed the building’s wooden interior two months before. Library of Congress.

(High-resolution versions of the photograph and catalog information are at the Library of Congress webpage here.)

The army commander on June 10 again proposed a move near Fredericksburg, when the Franklin’s bridgehead was still in place and garrisoned by a division from the Sixth Corps. That afternoon, Hooker telegraphed Lincoln with a more ambitious scheme for a southward attack: “throw a sufficient force over the river to compel the enemy to abandon his present position” around Fredericksburg and then undertake a “rapid advance on Richmond” while Lee’s army was still trying to move west and then northward. Hooker characterized his plan as “the most speedy and certain mode of giving the rebellion a mortal blow.”

Hooker’s two proposals seem at odds with his recently and prominently stated aversion, in General Orders No. 40, to making his main efforts through frontal attacks against strong positions. That order had been issued on the eve of the principal combats at Chancellorsville and predicted that “our enemy must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground.” After crossing at Franklin’s in December 1862 and April-May 1863, the Federals had both encountered and observed enemy defenses just beyond and to the west—along the grade of the RF&P Railroad, sunken in some places and raised in others, as well as on several cleared rises behind the railroad.

In June 1863, the Confederates again occupied these well-known positions in strength. Hooker’s telegram to Lincoln at nightfall on the 5th noted that they had responded to the assault-crossing by assembling “in great numbers from all quarters, and the more remote are still arriving.” On June 6 a brief revival of Union hopes for a general withdrawal of their enemies (evidently based on distant observations of Southern positions around the town of Fredericksburg) prompted orders for Sedgwick to essay a reconnaissance from the bridgehead and bring over the balance of his corps to support it “if necessary.” At midmorning of the 6th, Sedgwick responded from his headquarters, the house at the Bend: the enemy was “strong in our front,” having since sunrise positioned three batteries and rendered the current garrison of his bridgehead unable to “move 200 yards without bringing on a general engagement.” ”[I]t is not safe to mass the troops on this side,” he added. A surgeon in the 77th New York Infantry, who had joined the Vermonters and New Jerseyans on the south side of the Rappahannock, would write similarly of “the frowning batteries of the enemy on the hills in front…we could, with our glasses, discover great numbers of infantry at the base of the hills, half hidden by the low growth of pines.”

Determined Confederate picketing, which spiked into sharp combats that morning along the south and west sides of the bridgehead and along the northern side during the following days, did much to limit the Sixth Corps to a lodgment roughly rectangular in plan. It began on the Rappahannock below the pontoon bridges (two 400-foot spans having been completed on the 6th); extended west to the Richmond Stage Road/Bowling Green Road and past the ruins of “Mannsfield,” another Bernard family property; extended north along the west side of the road before crossing to the east side; and then, beginning at a point not far from the Ferneyhough house and barn at “Sligo,” followed the south bank of Deep Run east to the river just above the house at the Bend, overlooking the pontoons. That left Mannsfield inside Federal lines to become an evocative attraction for Northern soldier-sightseers and at least one photographer, and Sligo outside to become a roost for Confederate sharpshooters.

Detail from the image of Mannsfield above, showing at least three Union soldiers and, probably, a flag in background. Click to enlarge.

Lincoln and Halleck took a dim view of Hooker’s proposals of June 5 and June 10 for reasons that included the strength of the enemy’s position obstructing the Sixth Corps. Telegraphing back to Hooker on June 5 (and prior to Hooker sharing his growing doubt, that evening, that Lee’s army was indeed departing), Halleck suggested attacking the enemy’s “movable column first, instead of first attacking his intrenchments” while the Rappahannock isolated part of Hooker’s forces. Lincoln expressed similar reservations that same afternoon: the enemy at Fredericksburg “would fight in intrenchments and have you at disadvantage…man for man…while his main force would in some way be getting an advantage of you northward.” The Army of the Potomac, Lincoln added with one of his many, soon-famous lines, could become “entangled upon the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence and liable to be torn by dogs front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick the other.” In rejecting Hooker’s plan of June 10, Lincoln and Halleck cited the likely time-delay associated with besieging the Confederate capital, and emphasized, in Lincoln’s phrasing, that “Lee’s Army, and not Richmond, is your sure objective point.”

Hooker on June 12 ordered Sedgwick to abandon the Franklin’s Crossing bridgehead. Sedgwick’s men occupying it began withdrawing over the two pontoon bridges after nightfall on June 13 (and after a rare, “harmless” Confederate artillery bombardment late that afternoon). Benham’s engineers dismantled the last bridge before sunrise the next day. A half dozen companies of the 15th New Jersey Infantry remained behind as pickets and received orders to withdraw only after its removal. Union troops on the opposite shore employed individual pontoons to ferry “most” of them to safety by morning on June 14.

How should we understand Hooker’s proposals of June 5 and 10? Those were made in full awareness of 1) Lincoln’s general aversion to a crossing, in his message of May 14, 2) the bridgehead’s direct, westerly obstruction by the same Confederate defensive positions that had obstructed it during Chancellorsville—also referenced, generally, in the May 14 cautionary telegram from Lincoln, and 3) Halleck’s January 31 directive, the terms of which predisposed Hooker’s superiors to be skeptical of a southward attack against a northbound Lee. Also, a serious effort by Hooker to sell them on the June 10 plan could be reasonably expected to include at least passing mention of how he proposed to supply the operation against Richmond, and how Maj. Gen. John A. Dix’s Department of Virginia troops, positioned southeast of that city, might cooperate to secure logistical bases; advance in concert with; or otherwise support the approaching Army of the Potomac. (Dix, who remained under Halleck’s command, cautioned repeatedly that his force was “small” but certainly seemed willing to act, promising on June 4 “a diversion” to support Hooker; reporting on June 6 the ascent of a 5,000-man force up the Mattaponi River 45 miles from West Point to Walkerton, 23 miles from Richmond; and telegraphing Hooker on June 9 with a pledge for a two-pronged, westward move in greater force.) Yet Hooker’s proposal of June 10 did not offer proposals for such supply or coordination. A jaundiced view of Third Fredericksburg and the June 5 and 10 plans might therefore interpret those as means to restore his reputation for aggressiveness after Chancellorsville.

If Fighting Joe was indeed giving special priority to repairing his legacy, in other words, it would have been very helpful to have twice asked to return to the offensive while actually possessing a bridgehead on the enemy’s side of the Rappahannock (or, in the case of the plan suggested on the morning of June 5, 1863 being on the verge of possessing a bridgehead), thus enhancing the profile of the proposals even if those were ultimately rejected. Without question, Hooker’s record was on his mind and prominent in his conversation on June 10, when he read Provost Marshal General Marsena Patrick, as the latter recounted in his diary that night, “the orders given to Howard & Slocum at 9’30” on Saturday May 2,” putting “the onus on those Generals for the giving way on the right” at Chancellorsville.

Additional Federals pose in the Mannsfield garden in another detail from the image above. Click to enlarge.

In evaluating the feasibility (perhaps even as Hooker would have assessed it honestly) of the plans of June 5 and June 10, Historian Edwin B. Coddington a century later stopped short of detecting the cynical motive that I suggest but was highly dubious nonetheless, arguing that “Hill’s 15,000 men, well protected by earthworks, could offer stiff and perhaps prolonged resistance,” and if needed fall back to alternate points of defense nearer Richmond and reinforcement by George Pickett’s division and J. Johnston Pettigrew’s brigade. Coddington, after reviewing Hooker’s writings and statements about Chancellorsville and Third Fredericksburg (the latter term, again, mine, not Coddington’s), argued that the army commander harbored “an almost abnormal tendency to blame other people or circumstances for his failures.” Even before the abandonment of the Franklin’s bridgehead, Fighting Joe, along with his friend and chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield, began characterizing it privately as a great, lost opportunity that fell victim to Halleck’s disdain for Hooker generally and the constraints of Halleck’s January 31 directive specifically—an interpretation that Hooker made publicly in 1864 while testifying before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.

Noel G. Harrison

Next: part two of this article, including a more favorable view of Hooker’s motivation and planning for Third Fredericksburg, and a note on prior historical interpretations.

For both parts of this article I give special acknowledgment to John Kelley for his pathbreaking work on the June 1863 photographs, especially his observation of the abundance of leaves in those, as compared to leafless foliage of deciduous trees in images of the same area the previous month. The Center for Civil War Photography posted online Kelley’s “Hidden in Plain Sight: the First Photographs of the Gettysburg Campaign,” which was not available at that url at the time of an upgrade to this post in January 2021. However, the Library of Congress offers a summary of some of his research in its description of a May 1863 photograph of riverbank terrain just upstream from Franklin’s Crossing: “About this Item” here. I also extend gratitude to Charlie Lively, Don Pfanz, and Jake Struhelka for research assistance.

Sources in order of first appearance in captions and narrative above—Gettysburg-campaign designation in volume 27 of Official Records: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1 (hereafter “OR”), 27, pt. 1: 3 (quotations); “Third Battle of Fredericksburg” designations, 1884-1997: Alfred Theodore Andreas, History of Cook County, Illinois, p. 565; Janet Hewett, Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies: Record of Events: 45; George W. Kingsbury, History of Dakota Territory 4: 824; “Veterans Answer Last Roll Call,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 10, 1900; distinguishing June 1863 Rappahannock River photographs from those of April-May 1863: Library of Congress, “Fredericksburgh, from near Lacy House. Taken during the battle of May 3, 1863.” “About this Item.”; Porter’s similar suggestion in August 1862: OR, 12, pt. 2, supplement: 919; Lincoln’s May 7-May 14 exchanges with Hooker: OR, 25, pt. 2: 438 (first quotation), 440 (second quotation), 473 (third quotation), 479 (fourth quotation); Hooker’s May 28-June 3 caution: OR, 25, pt. 2: 534 (first quotation), 535 (second quotation), 536, 572, 573 (third, fourth, fifth, and sixth quotations), 593, OR, 27, pt. 3: 3, 4 (third quotation), 5; Sedgwick’s June 5 crossing-orders: OR, 27, pt. 1: 32 (quotation); pt. 3: 7; onset of Franklin’s Crossing fighting and participating units: Ira S. Dodd, The Song of the Rappahannock (1898), pp. 145-154; James C. Edmonds and Jack C. Waters, A Small But Spartan Band: The Florida Brigade in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, p. 58; Dale Floyd, ed., “Dear Friends at Home”: The Letters and Diary of Thomas James Owen, Fiftieth New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment, During the Civil War. Engineer Historical Studies No. 4; “From the Army of the Potomac; A Daring Reconnaissance Made Across the Rappahannock…” New York Times, June 8, 1863; Ed Malles, ed., Bridge Building in Wartime: Colonel Wesley Brainerd’s Memoir of the 50th New York Volunteer Engineers, p. 152 (quotations); George Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps, pp. 217-281; Gilbert Thompson, The Engineer Battalion in the Civil War, rev. by John W. N. Schulz, No. 44, Occasional Papers, Engineer School, United States Army (1910), pp. 34-35; Federals’ descriptions of Confederates’ fortifications: Dodd, pp. 149 (third quotation), 152 (first, fourth quotations), 155 (second quotation); Noel G. Harrison, Fredericksburg Civil War Sites 2: 70 (sixth quotation); Malles, p. 151 (fifth quotation),; OR 27, pt. 1: 676 (seventh and eighth quotations); Position occupied by a part of the Army crossing south of Fredericksburg. Made by Sergt. Myers June 7, 1863, Gouverneur Kemble Warren Papers, New York State Library; third crossing for 26th New Jersey: Dodd, p. 145; the terrified casualty, the uninjured coward: Dodd, pp. 160-162; the momentary coward: Dodd, pp. 162-163; the born hero: Dodd, p. 159; the redeemed hero: Dodd, p. 160; casualties for June 5 crossing: “From the Army of the Potomac; A Daring Reconnaissance Made Across the Rappahannock… ”; Malles, p. 154; OR 27, pt. 1, pp. 33, 677; Stevens, p. 218; Thompson, p. 35; Samuel Toombs, New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign, p. 25; Waters, p. 58; Union disputes over post-combat laurels: “From the Army of the Potomac; A Daring Reconnaissance Made Across the Rappahannock… ”; Malles, p. 153 (seventh quotation); OR 27, pt. 1: 677 (first quotation); OR 27, pt. 3: 63 (eighth and ninth quotations); Toombs, pp. 21 (third quotation), 22 (second quotation), 25 (fourth and fifth quotations), 26-31, 32-33 (sixth quotation); Hooker’s June 5 proposal to “pitch in”: OR 27, pt. 1: 30 (third, fourth, and fifth quotations), 31, 32 (second quotation), 33 (sixth quotation); OR 27, pt. 3: 11 (first quotation); Hooker’s June 10 proposal: OR 27, pt. 1: 34; General Orders No. 47: OR 25, pt. 1: 171; April 1863 fire at Mannsfield: Harrison 2: 80; strong Confederate position containing Union bridgehead and Sedgwick’s reconnaissance: OR 27, pt. 1: 33 (first quotation); OR 27, pt. 3: 12 (second and third quotations), 13 (fourth and fifth quotations); Stevens, p. 219 (fourth quotation); ongoing picket fighting, configuration of the bridgehead: Dodd, pp. 186-192; Harrison 2: 69, 76-77, 100-101, 103-104; OR 27, pt. 1: 677; Position occupied by a part of the Army crossing south of Fredericksburg. Made by Sergt. Myers June 7, 1863; Stevens, p. 219; Vermont (pseud.), “Letter from the First Brigade. Before Fredericksburg Heights, Va.,” Burlington Daily Times, June 13, 1863; Lincoln’s, Halleck’s responses to Hooker’s proposed moves: OR 27, pt. 1: 31 (first, second, third quotations), 35 (fourth quotation); bridgehead abandoned: Alanson Haines, History of the Fifteenth Regiment New Jersey Volunteers, p. 70 (quotations); OR 27, pt. 1: 226; OR 27, pt. 3: 73; Dix’s pledges and operations: Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, pp. 100-101; OR 27, pt. 3: 6 (quotations), 20, 44; Patrick, Coddington, and Hooker’s legacy: Coddington, p. 53 (third quotation); Marsena Rudolph Patrick, Diary, June 10, 1863, Library of Congress, quoted in David S. Sparks, ed., Inside Lincoln’s Army: The Diary of Marsena Rudolph Patrick, Provost Marshal General, Army of the Potomac, pp. 256-257 (first and second quotations); Hooker and Butterfield only supposed lost opportunity: Coddington, pp. 83, 84 (quotation), 97; OR 27, pt. 3: 175; Patrick, Diary, June 13, 1863, in Sparks, ed., p. 258.

Is it possible to connect the photographic view from the NY library with the work “A Mystery Photograph No More.” I’m speaking about the left – top section of the photograph.

Last thought – are there any efforts to preserve what is left of Franklin’s Crossing. The aerial image is quite profound. It is almost like a nightmare to see another Walmart alongside of an important Civil War historic site.

I visited this site last month for the first time. My GG GF was in the NJ 26th and fought in the post-enlistment engagement. We are very interested in preserving whatever we can of this site and are willing to provide the funding. If you know of anyone who can provide guidance, please let me know. Walmart has been not real helpful.

Noel,

This is great material and indeed shows how easily hindsight bias can allow a handy via from one larger element in time to another. Indeed, no one at that time on the Union side could have considered this the beginning movements to pursue Lee on his way north. Characterizing this as “Third Fredericksburg” is really a step forward in the scholarship. I applaud your take on this. Excellent analysis.

May I point out something, and perhaps you have, but I missed it? When you mention the low water level in the river for a period, the New York Public Library image seems to illustrate that by the presence of a large sand bar and much shorter pontoon sections. The June 5 date you supply is validated by that apparent evidence.

Again, fantastic work. Congratulations.

John Cummings

Superb analysis, Noel. A good historian finds new ways of looking at old information and you can certainly be characterized as a good historian. I especially appreciate that you looked for any planned follow up as a way to gauge the seriousness of Hooker’s effort. Logistics is never an after thought to military men and ought not to be one to military historians. Nicely done. I look forward to Part 2.

Thanks, all, for the thoughts and kind words. John K.: I don’t have a tiff version of the NYPL image. I figured that you’d be ordering one sooner or later; yours would be about the best-qualified pair of eyes to give the tiff a good looking over to see what you can find, especially as it relates to other photos of the area. I lack the background and type of involvement with the site to address your preservation question, by the way, but I do know that a variety of interested folks have certainly raised its profile in the past year or two, including my colleagues garnering front-page newspaper coverage for their tour of the site this May, and county and business leaders who facilitated the tour. John C.: Good observation about the water-level being altered downstream as well as upstream from Fredericksburg. Looking at the Library of Congress photo under hi-rez, my sense is that the narrower stretch of water is actually a longish pool on the lowest level of the riverbank on the Spotsylvania side. Noel

Noel,

Yes, you are correct, the pool of water is slightly visible in the LC image behind the left hand tree cluster, and the foreshortening gave the impression of a narrower passage. It was difficult to discern details of the low-res image from the NYPL. High resolution scans have changed our world.

John

I believe that sketch isn’t of Confederate defenders, but Union troops sheltering on the reverse side of the rifle pits after the crossing.

Stu, Great observation. For quite some time after first seeing the sketch, I had also assumed that the troops were Federals, my notion being encouraged by the dominant style of headgear as well as the configuration of the earthwork. Then I noticed that Waud had followed his usual practice and supplied a narrative to Harper’s, whose editors then published it along with the woodcut version of the sketch in their June 27 issue. The narrative states that the Union artillery on June 5 “did magnificent practice; hardly a shot missed the earth-work; its defenders, the Second Florida, were kept enveloped in smoke and dust; and yet so great a protection is a little bank of earth, that not a man was killed.” Supporting evidence for Waud’s subjects being Confederates comes from the absence of Confederate artillery fire in those Union narratives of the events of June 5 that I’ve seen. A Jerseyman reported “only few feeble shots” from the Confederate infantry once the top of the bluff was gained, while Wilbur Fisk, who came across with the 2nd Vermont later that same day, included the following in his summary of action on both the 5th and the 6th: “No doubt the rebels had batteries that could have annihilated us…but for some reason they remained quiet.” Perhaps the men in the sketch are sheltering behind the rear or western side of what was variously described as “a small fort” or “the little fort,” apparently situated just to the rear of the riflepits. Noel

This does make a lot of sense, especially with the lack of Confederate Artillery in action.

At the moment one of my sources had the NYLibrary image as originating at the Library of Congress. I checked with the Library of Congress and they do not have this image. The first source I know of was Mark Katz. I wish the Library of Congress had that image. In August, 2004, when the Center for Civil War Photography had their Seminar in Fredericksburg, I gave a talk titled Embedded with the Troops, Photo Journalism in the Civil War and I used the NYL image to show the row boats on the east side of Franklin’s Crossing and to coordinate it with O’Sullivan’s view that was mislabeled by Alexander Gardner. At that time, the source was Mark Katz and I am assuming he got it fromthe NY Library.

I’ll be happy to share that power point presentation.

Here’s another version-only Mansfield is misidentied as Bernard House!

http://www.americancivilwarphotos.com/category/battles/battle-fredericksburg

Hello, Thank you for reading and for your comment. “Bernard” is actually accurate since that was the name of the owner of Mannsfield. Noel

Just researching a civil war letter I have acquired and led me to this blog It’s late, but I believe it gives some details of the action referred to in the above.

Unfortunately, I am having some difficulty identifying the soldier who wrote the letter. Originally the letter was attributed to Thomas Nicholson of the 140th PA. But in reading the details it becomes evident that this is referring to the 6th Corp. There is a reference to the 62nd NY and to a cannon ball going through Gen Newton’s tent. There was a Nicholson in the 98th PA 3rd Brigade 3rd Division 6th Corp, but not Thomas. We may never know the soldier as he may have assumed a “nom de guerre”.

At the bottom of the first page it states ” On the ninth nothing of importance happened; in the evening a thousand men were detailed out of our Brigade to work on a rifle pit on the other side of the river.” Top of the second page says On the evening of the 10th we came over the river & drew up in position behind the rifle pit near the Bernard House.

I can forward scans of the letter.

Rick, Thank you for reading, and for sharing that. Unfortunately, the relatively long duration of the June operation at Franklin’s, and the paucity of my free time, allows me to explore mainly the events at the beginning and end of the bridgehead’s lifespan, and then only occasionally. But no doubt June 10, 1863, and other days in-between, saw interesting and significant events. We are always grateful for copies of materials not already present in the park’s research archives; my thanks in advance if you can indeed share copies of what you have with our staff historian, Don Pfanz, at the email Donald_Pfanz [at] nps.gov. Noel H.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

I visited the Franklin’s Crossing site by boat earlier this year. The cliff is clearly visible with it;s white sandy look that is characteristic of cliffs on the Rappahannock., and there is an old road trace down there.The river has been dredged over the years, and there is one of those box like dredging dykes in the water on the Spotsylvania side, right where you have mapped the bridges. This area has been heavily abused by the former FMC Plant that was here. Preserving the sight is possible. You can’t see Walmart for the trees. I got far to the Stafford side in my boat, and it was easy to see how a crossing here would have unfolded compared to your map.

Mr. Harrison, this may be a long-shot but I am reaching out to see if you have any more information for the property named “Sligo.” My husband and I purchased the home this past summer and I have started researching the property as well as the existing structure. My current source of knowledge is the WPA from the 1930s but I realize given the length of time between the Civil War and the report that some information may be inaccurate. I was given your name by either Mr. Staunton or Mr. Walker while I was visiting the archives at the Fredericksburg courthouse. Thank you for your time!

Thank you for the read, and welcome to the area.

Searching under Sligo or the names of its owners in the following online guides–in the event some or all are new to you—should bring you some nice results for follow-up at the respective archives here in Fredericksburg. (I did not include the guide for the Historic Court Records, since you’ve already visited there.)

-Central Rappahannock Heritage Center: https://crhc.pastperfectonline.com/archive

-newspapers on microfilm in the Virginiana Room the Caroline St. branch of the Central Rappahannock Regional Library: http://fbgresearchindxes.umw.edu/newspapersearch.asp

-other resources: http://resources.umwhisp.org/fredburg.htm

Noel H.