from: Harrison

My previous article of this miniseries introduced Union veteran Morris Schaff and his authoring of The Battle of the Wilderness, the first book on its subject. That article also began considering why Schaff’s goal of writing careful, conventional battle history remains virtually unknown today. When we compare his ambition to the same ambition embodied in John Bigelow’s book, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, published the same year, 1910, and destined to garner wide respect for evaluating the tactics and grand tactics of another local battle, the obscurity that befell Schaff’s project is all the more striking.

The article below explores the principal, ironic impediment to Schaff’s hope of being remembered for his conventional history: his book’s parallel, unconventional goal of understanding the battle and its participants as affected by activist spirits and ghosts, and intelligent, even compassionate, vegetation. As I noted earlier, a critic who reviewed Schaff’s book in 1911 marveled at an author “who, while framing a military treatise, can at the same time make it a new ‘Alice in Wonderland.’” A second reviewer, commenting on his book in The Dial in 1912, worried that the pairing of very different interpretive methods was “a stumbling-block” for many readers. The Dial critic went on to relate the response of a “distinguished fellow-soldier” to Schaff: “When you get done with your poetry and get down to history you will write a valuable book.”

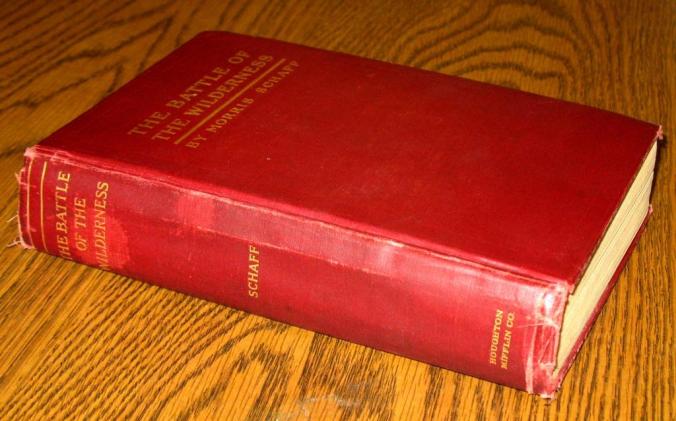

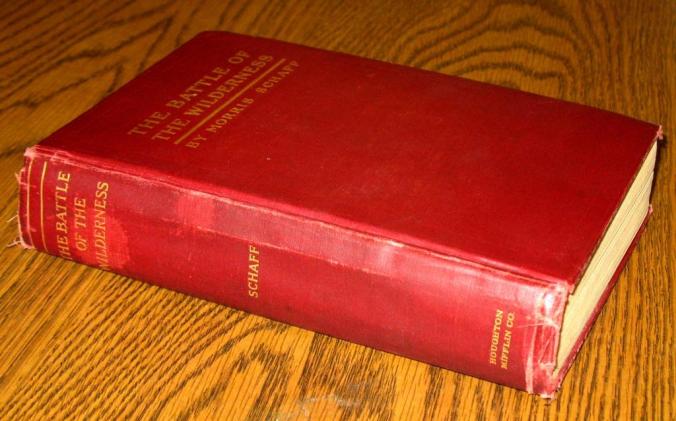

Marginalia and an inscription in this copy of Morris Schaff’s book indicate that 49-year-old Franklin J. Roth read it over the course of three weeks in the fall of 1912. A 1920’s newspaper article described Roth as president of the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania School Board and “a collector of old documents and historical data.” Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park library.

If Schaff’s diversions into the supernatural had been less prominent, readers might have understood those as efforts to enliven the book with analogy and allegory, or to achieve other purposes common among writers of his era. For instance, some of Schaff’s passages reflect the view, shared by many of the Civil War generation, that battlefield death could bring nobility, individual peace in the Christian afterlife, and North-South reconciliation. His book at one point has the allegory of Death encountering the mortally wounded Lieutenant Colonel Alford Chapman of the 57th New York Infantry; likely at no other place in the Wilderness had Death “met more steady eyes than those of this dying, family-remembering young man.” At another juncture, the spirits of dead soldiers, from both armies, rise “above the tree tops…a great flight of them towards Heaven’s gate…. [T]wo by two they lock arms like college boys and pass in together; and so it may be for all of us at last.”

Yet Schaff’s supernatural characters appear even more dramatically, across some 25 per cent of his book, in repeated interventions that alter battle outcomes and soldier experiences. For starters, there’s “The Spirit of the Wilderness,” which in turn has the capacity to conjure The Spirit of Slavery. Schaff at several points describes The Spirit of Slavery as a single being and at another as “a resurrected procession of dim faces” moving “in “ghostly silence.” The Spirit of the Wilderness is determined to punish the Confederacy for the miseries suffered in the same forest a century earlier by those people while alive and enslaved on Alexander Spottswood’s vast local landholdings (and more generally by all slaves since then).

Even media not typically hospitable to supernatural interpretation conveyed the view that Stonewall Jackson’s mortal wounding in the Wilderness at Chancellorsville was an eerie, extraordinary event. Detail from Benjamin Lewis Blackford, “Part of Spotsylvania County,” Gilmer Civil War Maps Collection, University of North Carolina.

(Click here for hi-rez version.)

First, The Spirit of the Wilderness in 1863 takes the life of Stonewall Jackson, who finds himself transformed into yet another specter haunting its depths. Then, a year later, the Spirit strikes down James Longstreet, “just as victory was in his [Robert E. Lee’s] grasp,” and in a battle where success was “absolutely necessary to save the life of the Confederacy.” Schaff’s very next paragraph describes the underlying forces at work, with “miraculous” by no means synonymous with “benevolent”:

Reader, if the Spirit of the Wilderness be unreal to you, not so is it to me. Bear in mind that the natural realm of the spirit of man is nature’s kingdom, that there he has made all of his discoveries, and yet what a vast region is unexplored, that region among whose misty coast Imagination wings her way bringing one suggestion after another of miraculous transformations….

Continue reading →