from: Harrison

With the park having concluded sesquicentennial observances of the four battles within its historical bailiwick, I’d like to consider how those engaged the imagination once the guns fell silent. Readers of this blog may recall my interest in the literary aspects of early commentary on the fighting. What follows is adapted from a “History at Sunset” program that I presented recently on supernatural imagery, used by some chroniclers of the Civil War generation in describing Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and the vast tract of woodland encompassing both.

I drew inspiration from Union veteran Morris Schaff’s The Battle of the Wilderness, published in 1910. It’s the most unique history I’ve read of a Civil War battle. It’s also the first book to be devoted solely to the two-day clash of May 1864, not to be supplemented in that category until Edward Steere published The Wilderness Campaign half a century after Schaff’s volume appeared.

Houghton-Mifflin’s advertising for the serialized version of Schaff’s book, Atlantic Monthly, March 1909.

Schaff’s publisher, Houghton-Mifflin of Boston and New York, had serialized the book in their magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, beginning in June 1909. Schaff’s study was thus distributed widely and essentially twice. (The publishers seemed delighted with its reception, inviting him to write an article-length sequel and running that in Atlantic in 1911.)

Readers across the country had this first-ever, book-length encounter with the Battle of the Wilderness in a profoundly strange atmosphere. Schaff’s text swerved back and forth from the conventional to the unconventional, from straightforward terrain- and tactics analysis to supernatural interventions. In 1911, a reviewer for The Nation spent several column-inches trying to finalize his thoughts about Schaff and concluded, “We applaud the writer who, while framing a military treatise, can at the same time make it a new ‘Alice in Wonderland.’” In this blog post, let’s consider the conventional and even “cutting-edge” aspects of The Battle of the Wilderness. These highlight through contrast the weird aspects (next post), as strange now as in 1910.

At the battle of the Wilderness, the 23-year-old Schaff served on the staff of Fifth Corps Commander Gouveneur K. Warren. Some of Schaff’s detailed descriptions of what he saw would become popular among later historians, especially his detailed, vivid recollection of Warren meeting with other staffers in the Lacy House, “Ellwood,” and urging them to reduce the casualty return for his corps.

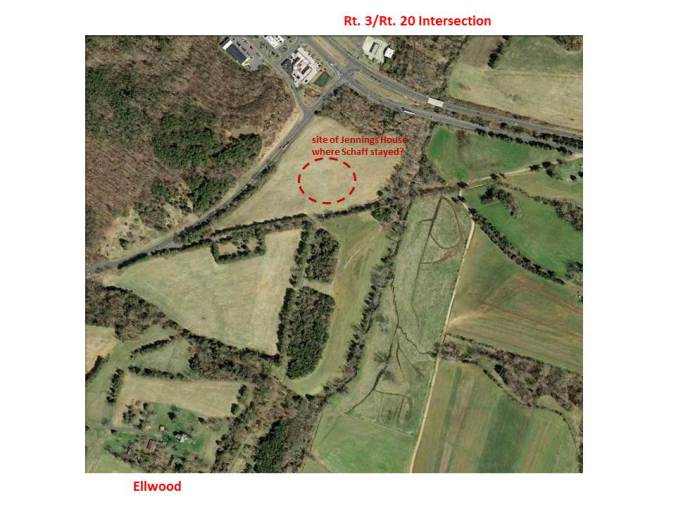

Ellwood and environs. For visitors to the Wilderness today, Morris Schaff is probably best known for his striking account of an episode in the Lacy house, “Ellwood,” involving a casualty tally and a brief but vivid description of one of its rooms. Virtually unknown is his ambitious effort to understand many other aspects of the battle. This entailed Schaff making at least one postwar visit, when a Mr. and Mrs. Jennings hosted him, possibly at a now-vanished structure that appears on a 1930’s map.

Largely forgotten today, however, is Schaff’s intention to offer a book of history—a straightforward chronicle of things he didn’t see at the Wilderness as well of those he did—not merely a compilation of quotable observations. Yet as the decades passed after 1910, his study acquired little of the gravitas of, say, another that had appeared that same year, about another battle fought mainly in the same forest: John Bigelow’s The Campaign of Chancellorsville. I suspect that Bigelow’s vision of a serious tactical study found lasting realization in part because it was supported by abundant troop-movement maps. Schaff’s book, in contrast, offered only one detailed map of the battlefield and none showing troop movements. At several junctures, moreover, he denies any intent to offer tactical narrative and analysis—leaving that to “the bass-drum wisdom of theoretical strategists”—yet soon returns to pursuing that goal, as noted by the puzzled reviewer in The Nation.

Schaff compensated for the absence of troop-movement maps by presenting written accounts of maneuvers and combat. Roughly half of his study is careful, chronological history on both the grand-tactical and tactical levels. Never content to rely upon his own, limited experiences, he notes many instances where he talked or corresponded with veterans, researched in the Official Records, and consulted other written accounts by participants on both sides. Schaff’s coverage of the first day’s fighting for the Brock Road-Plank Road intersection, for example, cites diaries and regimental histories from five different regiments in four different Confederate brigades.

For the principal battlefield-map, Schaff’s book used a slightly modified version of this depiction of the Wilderness battlefield, prepared in 1867 under the direction of Nathaniel Michler. A Major of Engineers during the battle, Michler would figure in a vignette in the book. Courtesy National Archives.

Across those portions of the book that compose its conventional, tactical component, real terrain and real decisions and real maneuvers, not supernatural factors, bring real outcomes. Most important, this is the earliest extended history of a Fredericksburg-area battle that to my knowledge urged readers, by repeated examples in the main narrative, to visit the battle’s site. Schaff saw historical interpretation as more than an exercise in sticking pins into maps while following a text—the specific recommendation in the preface to Bigelow’s Chancellorsville (underscored in that preface with a small picture of a unit-label transfixed by a pin).

Schaff thus occupied the front rank of one advance in historical endeavor, sharing the go-and-look approach of early advocates of military staff rides on battlefields and of establishing permanent public access to those places as national parks (although his book mentions neither movement specifically). As preparation for writing, he revisited the Wilderness battlefield at least once, in May of 1908 or 1909. Besides traversing much of the old combat area, he spent all or part of one evening at the home of “Mr. and Mrs. Jennings”—likely the postwar farmstead of Robert and Willie Jennings near Ellwood. Schaff evidently planned his 1908/1909 return for the period when the vegetation would have about the same consistency as it did 45 springs before.

This dynamic but rarely seen Alfred Waud sketch depicts the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves fighting in or near the Chewning Farm clearing, May 5, 1864. The terrain and historical what-if’s of the Chewning area fascinated Morris Schaff. Courtesy Library of Congress.

(Click here for hi-rez version and full transcription of Waud’s caption.)

Schaff’s tour of the battlefield included a trip to the Chewning farm:

The ground…rises up sharply to its rather high, dipping, and swerving fields, which when I saw them last, were beginning to clothe themselves in springtime green.

…

Let anyone stand on the rolling fields now and he will recognize at once their value to us could we have held them.

…

Had Warren’s orders to Crawford [halting him at Chewning’s] been delayed twenty or thirty minutes, the entire day’s operations would have been changed, for his advance would have brought him in immediate contact with the Confederate infantry and Lee’s plans would have been disclosed…. It is all conjecture what…moves Grant would have made in that case, but the chances are…Hancock would have been diverted to the junction of the Brock and Plank roads; that Getty would have been pushed immediately to the Chewning farm, and with Hancock forcing his way to Parker’s store, and those open fields firmly in our possession…would have made Lee’s position very critical. If Warren…had continued up the road to Crawford, his quick eye would have taken in the strength an importance of the Chewning plateau at a glance, and he would have…[brought] Wadsworth right up to hold it….

Schaff also included the area between the Brock/Plank intersection and the Tapp field on his tour itinerary. Although the ground at the intersection proper was generally flat, he nearby found drainages that flowed around “dead leaves and dead limbs and around low tussocks, crowned when I saw them…with blooming cowslips” and together warped the terrain into a series of low elevations. Separated by stretches of “thickety morasses,” the rises extended roughly perpendicular to the Plank Road southwest of the intersection. The subtle corrugation, Schaff concluded, gave the Confederates “splendid standing ground…almost invisible within forty or fifty yards” from which to resist Union counterattacks on the battle’s first day.

Woods transitioning from thin to dense in the area today of the northern fringe of Saunders’ field during the Civil War. More important than Schaff’s own interpretations of the terrain he encountered in 1908/1909 was the fact that he urged readers, by his example, to visit the battlefield themselves. Photo courtesy Greg Chapman.

A visit to another part of the old battlefield helped Schaff understand the difficulty that the Union Sixth Corps had experienced in attempting to support the Fifth Corps on May 5, 1864. He found that the woods around Saunders’ Field (itself becoming overgrown with “houstonias, flaming azaleas, broom-grass, struggling pines, cedars, oaks, sumac and sassafrass”) were most dense north and east of its wartime limits—a zone that included the area where the two corps were supposed to have made an early connection:

Upton’s men, the left of Wright’s division of the Sixth Corps, are elbowing their way through a tangle like that Ayers [commander of the right-flank brigade of the Fifth Corps] is worming his way through, trying to overtake and connect with him. In fact, when I was there last spring Upton’s ground seemed to be the worse, but both were bad enough. Wright’s second brigade…is on Upton’s right and across the Flat Run Road (they too were in the network of undergrowth.)

In stressing what would later be called “ground-truthing,” built upon careful historical research, Schaff not only echoed some of his contemporaries—the early staff riders and park advocates and planners—he blazed paths for the countless historical interpreters and their audiences who would gradually follow to the Wilderness battlefield, however unaware of his pioneering efforts…to the Chewning Farm, the Brock-Plank intersection, and Saunder’s field. Last but not least on that list is Ellwood, inspiration for one of his book’s most appealing passages:

Great, majestic, and magnanimous Night has come down, covering the Wilderness and us all in mysterious silence. Let us take a couple of these folding camp-chairs and go out and sit in the starlight on the lawn of the old Lacy house. Here is my tobacco-pouch; fill your pipe, and I’ll try to convey to you the situation at this hour on the field, and then we will turn in.

Noel G. Harrison

Next: Schaff’s Going Gets Weird: a Titanic Explosion, Murder, and Supernatural Imagery

Special thanks to Greg Chapman for photographic assistance. For a fun, informative look at the Chewnings and the farmstead on which Schaff and so many other strangers fixated, see this post by longtime park friend Pat Sullivan. For an eloquent appreciation of Morris Schaff, I highly recommend Stephen Cushman’s fine book on the Wilderness, Bloody Promenade: Reflections on a Civil War Battle (Schaff discussed on pp. 183-87). As noted above, I find a “normal,” tactical study prominent in Schaff’s account of the Wilderness, although one that he unspools alongside less conventional interpretations. Cushman, however, sees mainly the latter—Schaff’s “spiritual world” and even his “transcendentalism,” aspects to be covered in my next post.

Sources in order of appearance above—Schaff’s article-length sequel: “A Dream-March to the Wilderness,” Atlantic Monthly 107 (May 1911): 632-640; 1911 review: The Nation, 92 (Jan. 19, 1911): 64-65; 1930’s map showing possible Jennings location: Fredericksburg-Spotsylvania Battlefield National Monument, Virginia, 1931-34 (link here); Warren and the casualty return: Schaff, pp. 209-10; Schaff’s denials of a tactical focus: Schaff, 51, 65, 202; Schaff’s careful research: Schaff, pp. 29, 97, 115-16, 125-29, 133, 140, 144, 146, 157-58, 194, 201; five Confederate regiments in four brigades: Schaff, pp. 179, 195-96, 216; association with Michler: Schaff, 45, 135, 202; Bigelow’s pins-recommendation: John Bigelow, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, pp. xiii, (A footnote on pp. 384-85 is Bigelow’s only mention of personal, on-site analysis of specific terrain: an evaluation of the state of preservation of the stone wall at Fredericksburg.); early staff rides locally: Jay Luvaas and Harold W. Nelson, Guide to the Battles of Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, pp. 191, 193; early battlefield-park advocacy locally: Joan M. Zenzen, At the Crossroads of Preservation and Development: A History of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Administrative History, pp. 27-31; date(s) of Schaff’s postwar visit: Schaff, pp. 94, 100, 139, 153 (these date-references also in serialized version of 1909); Mr. and Mrs. Jennings as hosts: Margaret C. Klein, Tombstone Inscriptions of Orange County, Virginia, p. 47, Schaff, p. 221; 13th Pennsylvania at Chewning’s: O. R. Howard Thomson and William H. Rauch, History of the “Bucktails,” pp. 292-95; Schaff visits and evaluates Chewning terrain: Schaff, pp. 130, 132-33; visits and evaluates the Brock-Plank-Tapp terrain: Schaff, pp. 169-71, 183-84, 193; visits and evaluates Saunder’s field-area terrain: Schaff, pp. 139, 149-50, 164; addresses the reader at Ellwood: Schaff, p. 212.

Can’t wait for the next post. 🙂

Thanks for reading, Grace. Noel

Thanks for putting this out there, Noel. I had not heard of Schaff’s book before. Was the Chewning farm mentioned here “Mount View,” the home of Absalom Herndon Chewning?

Always great to get your Wilderness-specific read and take, Pat. Yes: Schaff was referring to the Mount View Chewning farm. Noel

Great article, Noel.

Thank you, Gordon. Always great to see you on here. I enjoyed our chat at the visitor center. Noel

Thanks for introducing me to Schaff and his work !

Great post, Noel. As always, you find nuggets and generously share them. I am reminded of your own efforts to ground-truth the lost landmarks of places within and around FSNMP. Didn’t realize you were in such good company.

Erik

War is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

Hello! Very nice article about Schaff’s book. You describe how Schaff illustrates the battleground geography with a modified version of Nathanial Michler’s 1867 map and show a portion of a map of the battlefield [ https://npsfrsp.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/michler-wilderness-na-med-2.jpg ].

The copy of the 1867 Michler map I was able to download from the Library of Congress [ https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3884w.cw0665800/ ] doesn’t seem to match the same detail as the map portion you display in your article. My downloaded map shows Keaton (or Caton) run draining the area immediately west of the Confederate entrenchments at the Orange Turnpike (i.e., draining to the north). A contemporary map by Maj. C.W. Howell shows this area is draining into a tributary of Wilderness Run, to the south of the Turnpike. Most modern topo maps also indicate the drainage into Wilderness Run.

The portion of the map that you show also shows the southern Wilderness run drainage – is this another version of Michler’s map?

Thanks.

Dave, Thank you for the read and for your kind words. As noted in the map’s caption in the blog post, its source is the National Archives, rather than Library of Congress. The Archives has been reformatting their online Civil War maps and photos over the years since I’ve been blogging; the full citation for that version of the map is currently at this url: https://research.archives.gov/id/305605 (I noticed this evening that the zoom on that page doesn’t seem to be functioning, at least on my computer, so there is currently more detail when you click on the version used in my blog post).

This is the only version of the 1867 Michler map that I use. But as the chief repository for the work and records of military cartographers, the National Archives may have other materials on Michler and his fellow mapmakers, searchable via the box at the top of that same webpage.

Best, Noel

Hi Noel –

Thank you for your reply and the link to the NARA website. I was able to view and download their image of the Michler map (“Reconnoissances During the Actions of the 5th, 6th, and 7th of May 1864”) but their system only produces a max image size of 890 x 1200 with a resolution of 120 dpi. The resolution would be fine except that the size limitation blurs the image detail.

The Library of Congress Michler map that I have (“Wilderness from Surveys” … 1867) is different than the NARA “Reconnoissances” map, especially in the vicinity where the Confederate entrenchments intersect the Orange Turnpike at Saunders Field. Of particular interest on the “Reconnoissances” map is the small farm road just west of the entrenchments which starts at the turnpike and runs south to the area of the Higgerson farm; this road is not shown on the 1867 map. Also, the drainage in that area appears to flow south to Wilderness Run on the “Reconnoissances” map vis drainage into Keaton’s run north of the pike that is shown on the 1867 map.

The “Reconnoissances” map is more consistent with the survey map of Maj. C.W. Howell (1865) and the drainages indicated in modern topographic charts.

The map image on your blog post is a partial cut out from the original – do you have a high resolution, full sized scan of this Michler “Reconnoissances” map?

Thanks,

Dave Deatherage

This is just magnificent! As someone who literally lives inside of the Wilderness Battlefield I hike these locations all the time. But more than just an avid hiker interested in using the battlefields as a means of exercise, I am a student of history. I am totally enthralled with the local history here. And it goes back not only to Gov. Spotswood and his German miners of 1711 colonial times, but to Native American villages along the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers. So many battlefields within very close proximity. Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Salem Church, Spotsylvania Court House, Brandy Station, and many smaller skirmish spots, encampment locations and nearby town occupations. Like the towns of Orange, Spotsylvania and Culpeper. I also continuously photograph the trails, antebellum roads, battlefields, antebellum homes. The NPS and battlefield preservation societies have done a great job of preserving our history here. Remnants of the battles and history are still very visible. Sometimes I just feel an eerie presence as if the soldiers were still there. The visuals are awesome. As Morris Schaff has stated, “go visit these sites”. I certainly will be reading his book in the near future.

Thanks,

Howard

Thank you for such kind words, Howard. I share your, and Morris Schaff’s, spiritual connection to our local history…and in the Big Picture timeframe, including but also beyond 1861-65. Noel