From Peter Maugle

What was Burnside thinking? The question has been posed by innumerable battlefield visitors, historians, and even Civil War veterans in regards to Fredericksburg. The notable Union defeat leads many to ponder the Federal commander’s intent. Burnside indeed had a plan, however its premise has been debated since 1862.

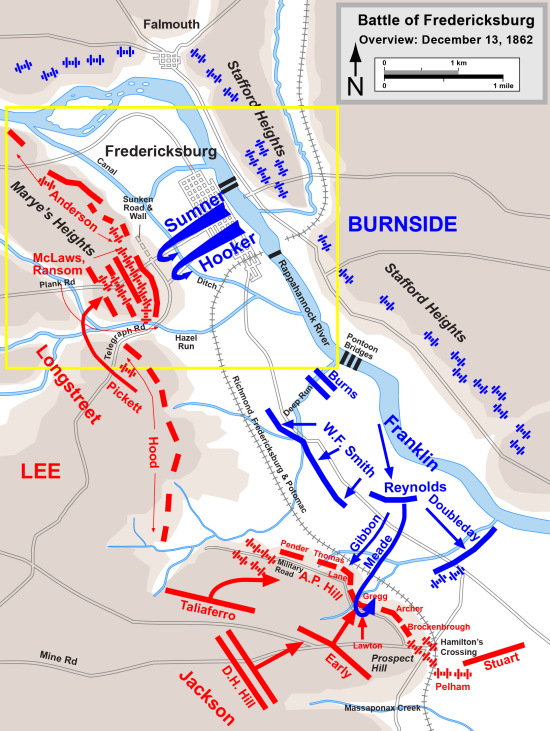

One hypothesis regarding the Union plan postulates a primary effort by Major General William Franklin’s Left Grand Division against the Confederate right, while Major General Edwin Sumner’s Right Grand Division conducted a diversion on the Confederate left at the Sunken Road and Marye’s Heights. On the surface, this notion appears to explain an otherwise misunderstood tactical plan. But is it really that simple? How did an intended diversion result in 30,000 troops launching all-out attacks for six hours? A closer look at the facts seems to refute the diversion theory.

To begin, consider the orders Burnside wrote on the morning of the battle. While they may lack clarity, these orders attempted to outline Burnside’s intentions. Here is the order issued to General Franklin on the morning of December 13th: [emphasis added]

“The general commanding directs that you keep your whole command in position for a rapid movement down the old Richmond road, and you will send out at once a division at least to pass below Smithfield, to seize, if possible, the height near Captain Hamilton’s, on this side of the Massaponax, taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open. He has ordered another column up the Plank road to its intersection with the Telegraph road, where they will divide, with a view to seizing the heights on both of these roads. Holding these two heights, with the heights near Captain Hamilton’s, will, he hopes, compel the enemy to evacuate the whole ridge between these points …”

The order does not designate primary or secondary attacks. Consequently, in his testimony to the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Franklin claimed he was unaware that his assault held any precedence.

Next is the order issued to General Sumner, which is similar to Franklin’s instructions: [emphasis added]

“The general commanding directs that you extend the left of your command to Deep Run, connecting with General Franklin, extending your right as far as your judgement may dictate. He also directs that you push a column of a division or more along the Plank and Telegraph roads, with a view to seizing the heights in the rear of the town. The latter movement should be well covered by skirmishers, and supported so as to keep its line of retreat open. Copy of instructions given to General Franklin will be sent to you very soon. You will please await them at your present headquarters, where he (the general commanding) will met you. Great care should be taken to prevent a collision of our own forces during the fog … The column for a movement up the Telegraph and Plank roads will be got in readiness to move, but will not move till the general commanding communicates with you.”

After the battle, Sumner testified to the Congressional committee, “I was ordered by the general commanding to select the corps to make the attack … They made repeated assaults … I do not think it a reproach to those divisions that they did not carry that position …”

Sumner did not mention any effort to distract the enemy, but rather he provided rationale for why his troops did not take their assigned objective, as was apparently expected of them. Surely, Sumner would have cited the intent of his orders if they had never stipulated success in the first place!

An eager contributor to the Congressional committee’s inquiry was Major General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Center Grand Division at Fredericksburg. Portions of his forces were engaged on both ends of the battlefield, and Hooker recalled, “But General Burnside said that his favorite place of attack was on the telegraph road. Said he, ‘That has always been my favorite place of attack.’ The army was accordingly divided to make two attacks.”

The most direct reference to the diversionary attack concept was during Franklin’s questioning by the committee. When queried about the potential for Union success, Franklin responded:

“It is my opinion that if, instead of making two real attacks, our whole force had been concentrated on the left – that is, our available force – and the real attack had been made there, and merely a feint made upon the right, we might have carried the heights.”

Franklin definitively asserted there was no diversionary demonstration, which in his opinion ultimately contributed to the failure of the plan. Admittedly, Franklin was under scrutiny by the committee and attempted to justify his actions. However, to declare a blatantly false statement would likely generate rebuttals, of which there were none. And as we have seen, this deposition by Franklin does not contradict any of the other testimonies.

Map by Hal Jespersen, http://www.cwmaps.com

Thus, it seems the actual plan was more complicated and nuanced than simply a main attack supported by a diversion. Burnside, in his testimony to the committee, stated:

“I wanted to obtain possession of that new [military] road, and that was my reason for making an attack on the extreme left. I did not intend to make the attack on the right until that position had been taken; which I supposed would stagger the enemy, cutting their line in two; and then I proposed to make a direct attack on their front, and drive them out of their works.”

In a letter to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, Burnside reinforced his goal of seizing the Sunken Road and Marye’s Heights: [emphasis added]

“I discovered that he did not anticipate the crossing of our whole force at Fredericksburg, and I hoped, by rapidly throwing the whole command over at that place to separate, by a vigorous attack, the forces of the enemy on the river below from the forces behind and on the crest in the rear of the town, in which case we could fight him with great advantage in our favor. For this we had to gain a height on the extreme right of the crest which commanded a new road lately made by the enemy …”

Regardless of Burnside’s ultimate intentions, much relied on how well he communicated them and if they withstood the changing nature of a fluid battle. While legitimate criticisms may be leveled on Burnside for those shortcomings, there is no basis to misconstrue the assaults on the Sunken Road and Marye’s Heights as diversions or anything other than what they were meant to be – genuine attacks.

Franklin, William B. A Reply of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin to the Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1863.

U.S. Congress. Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. 3 vols. Washington: GPO, 1863; 5 vols. 1865.

U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 vols. Washington: GPO, 1880-1901.