From Hennessy:

The Union winter encampment in Stafford in early 1863 teemed with life, but produced death on a daily, rhythmic basis. And death attracted entrepreneurs, intent on serving and capitalizing upon the desires of both the living and the dead. At least two embalmers worked within the Army of the Potomac that winter. They provided a full range of “vertically integrated” services (as we would say today), from caskets to the “disinfection” of long-buried bodies prior to shipment, to embalming of the recently dead. While it’s easy to scoff or flinch at such services, the embalmers filled a demand newly possible: sending the dead home to families for proper burials in their hometowns.

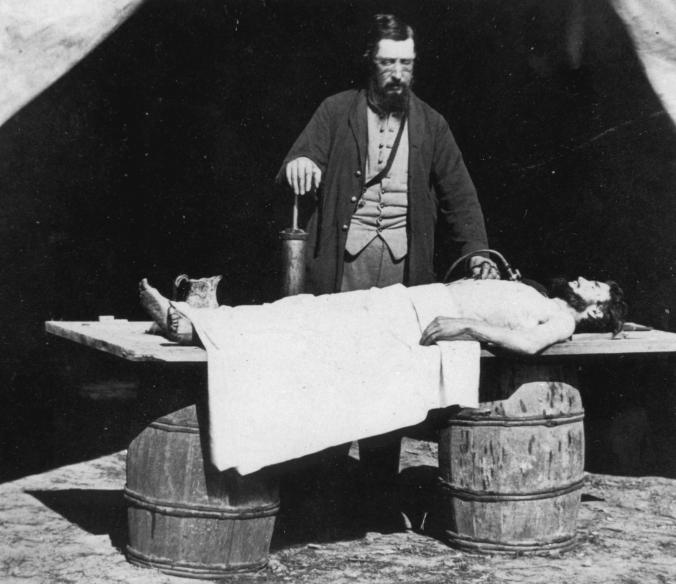

The improvised embalming shed of Doctor William J. Bunnell, “near Fredericksburg,” though precisely where is not known (certainly in Stafford County). Note the canvas intended apparently intended to turn a porch into a work space. The note on the back of this stereo card images says, “Here the bodies of the dead that were to be sent North to their friends were embalmed. More than a hundred bodies were sometimes brought here in one day. During the first battle of Fredericksburg…several hundred bodies were here at one time to be embalmed.” The latter claim seems highly exaggerated, as a small percentage of the dead from Fredericksburg were recovered, and a still smaller percentage of those were transported home for burial.

I recently came across a letter written by a member of the 35th New York infantry on March 10, 1863 that touched on the subject.

Each train carries away from here one or more dead bodies. Any of these have been disinterred from localities where they were placed after the great fight; and after being put through what is called the “disinfecting process,” they are transportable. Many of those who die from day to day are embalmed soon after death, and are thus rendered suitable for examination and burial at home, perhaps a thousand miles away. Dr. Burr, one of the chief embalmers for the army, is a very pleasant gentleman, and always takes pleasure in explaining his process. The force pipe, in his process, is introduced to the heart of the subject, and a powerful pump injects the preserving fluid through all the arteries. In cold weather there is no trouble in beautifully preserving the subject, but in warm season the failures are about one in ten. His price for privates is $50, including coffin, and for officers $100.*

Dr. Richard Burr, the embalmer mentioned in the New Yorker’s letter, demonstrating his method of embalming by injecting chemicals through the heart. In 1864, Burr was accused of embalming a soldier without permission, then refusing to release the body until the family paid the required fee.

Embalming involved the use of toxic chemicals that would prompt evacuations and the activation of HAZMAT units today. I’m not sure what the process of “disinfection” of long-buried bodies entailed (perhaps some of you do), but I suspect it’s a wash of the same chemicals used for embalming. Additional thoughts are welcome.

*The letter appeared in the March 17, 1869 issue of the [Watertown] Northern New York Journal.

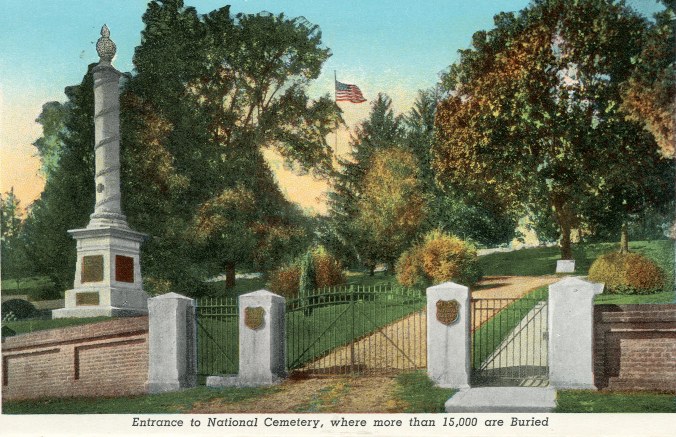

This National Cemetery, with its tidy rows, terraces, and beautiful landscape, is the nation’s attempt to remedy the horror and chaos of the battlefield and instead to accord dignity to those who fell. It’s a reflection of a nation’s effort to soothe its battered, even disbelieving soul in the aftermath of a carnage few would have imagined years before.

This National Cemetery, with its tidy rows, terraces, and beautiful landscape, is the nation’s attempt to remedy the horror and chaos of the battlefield and instead to accord dignity to those who fell. It’s a reflection of a nation’s effort to soothe its battered, even disbelieving soul in the aftermath of a carnage few would have imagined years before. But this place is more than simply the collection of individual stories; it is more than the sum total of our personal musings over the tragic fates of fathers, sons, husbands, and families (every one of them was a tragedy).

But this place is more than simply the collection of individual stories; it is more than the sum total of our personal musings over the tragic fates of fathers, sons, husbands, and families (every one of them was a tragedy).

From Hennessy: Here is stop 3 on Saturday’s Remembrance Walk, at the original stone wall. Greg Mertz delivered this text. For parts 1 and 2 click

From Hennessy: Here is stop 3 on Saturday’s Remembrance Walk, at the original stone wall. Greg Mertz delivered this text. For parts 1 and 2 click

Richard Kirkland was only 19 at Fredericksburg, with only ten months to live. He and his fellow South Carolinians joined the fight in the Sunken Road late that winter afternoon. Like his fellow Confederates, he endured the cold of the night after, and the sounds of the wounded left on the Bloody Plain.

Richard Kirkland was only 19 at Fredericksburg, with only ten months to live. He and his fellow South Carolinians joined the fight in the Sunken Road late that winter afternoon. Like his fellow Confederates, he endured the cold of the night after, and the sounds of the wounded left on the Bloody Plain. The distant Union troops—about 150 yards away—quickly saw Kirkland’s intent. No bullets whizzed his way. For 90 minutes, Kirkland moved about the field among the Union wounded, giving water, placing knapsacks as pillows—caring for chilled men lying in bloody muck. For 90 minutes, Kirkland did his work, then returned to the Sunken Road and its protective wall, unharmed.

The distant Union troops—about 150 yards away—quickly saw Kirkland’s intent. No bullets whizzed his way. For 90 minutes, Kirkland moved about the field among the Union wounded, giving water, placing knapsacks as pillows—caring for chilled men lying in bloody muck. For 90 minutes, Kirkland did his work, then returned to the Sunken Road and its protective wall, unharmed.