from: Harrison

Note: for magnification of a picture or map below, click on it, then select “Open in New Tab” (phone) or “Open Image in New Tab” (computer).

Among the contemporary drawings of the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, I find a little known panorama by artist-eyewitness Henri Lovie easily the most ambitious. With Battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862, he depicted in a single sketch the fighting at both ends of the battlefield that day–principal combat sites separated by four miles at the extremes. Lovie’s drawing measures four and one-half inches in height and nearly five feet in length. Beyond its own artistic power, it served as the main reference for a pair of grand-finale pictures in a striking sequence of eight wood engravings, or woodcuts, of the Fredericksburg campaign. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper published the eight over the course of five issues and four weeks, basing the other six woodcuts mainly on Lovie’s sketches as well and even incorporating the pictures into its editorial critique of the campaign. I only recently noticed his December 13 drawing in the digitized collections of the New York Public Library. The Library’s link to it and the means to magnify or download a high-resolution copy are here.

The right end of the sketch includes the only known—to me, at least—eyewitness drawing that looks northwest at the fighting outside Fredericksburg and in front of Marye’s Heights. For orientation, I made preliminary, estimated identifications of selected landmarks:

Detail from Henri Lovie, Battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. Annotation and color contrast by Noel G. Harrison.

(I share this portion of the sketch, and those below, to advance the educational purpose of this blog, and in accordance with the New York Public Library’s posted belief that the item is in the public domain under the laws of the United States.)

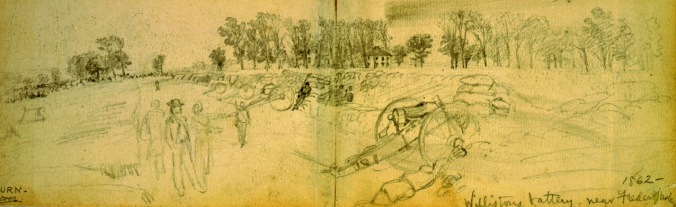

The left end offers what I believe is the only eyewitness sketch of the fighting in the opposite, southern zone of the battlefield that includes, albeit faintly, the Confederate artillery defending Prospect Hill as well as many of the Federals confronting the hill from east of the Richmond Stage Road:

Detail of Henri Lovie, Battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. Annotation and color contrast by Noel G. Harrison.

Lovie (1829-1875, born in Berlin, Prussia) sketched from a vantage point on the edge of the bluffs on the Stafford County (east) side of the Rappahannock River and near the pontoon bridges at Franklin’s Crossing:

Detail of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Battle of Fredericksburg December 13, 1862 2:00-3:00 P.M., Map 4 of 5, Historical research by Frank A. O’Reilly, Illustrated by John Dove, Revised and produced by Steve Stanley (2001). Courtesy Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Directional arrow at upper left; north is toward right on map. Lovie-related annotation by Noel G. Harrison.