From Eric Mink:

This begins a three-part post that will look at early collectors and exhibits of Fredericksburg’s Civil War history.

An earlier post, found here, took a look at Fredericksburg’s Museum of War Relics (1887-1891). The museum was actually a room in the Exchange Hotel that contained displays of Civil War relics and artifacts. Leander Cotton and William A. Hills ran the hotel and owned the collection. Their museum marked the first effort within Fredericksburg to display artifacts associated with the area’s Civil War history. The Cotton and Hills collection proved to be a good draw for the hotel and an early attempt to capitalize on toursim generated by the local battlefields. When the two men left the hotel business in 1891, they sold the collection to a Union veterans’ organization in Massachusetts. It wasn’t long, however, before another Fredericksburg merchant assembled his own impressive collection of war material and put it on display in his store. Like the Cotton and Hills collection, it too became an attraction with both local citizens and visitors to the area.

Bernard H. Jacobs emigrated from Prussia in the early 1860s and first settled in Richmond, Virginia. From there, he moved to Orange, Virginia and then on to the west coast. He returned to Virginia, finally making Fredericksburg his home in 1878. Jacobs opened a clothing store at 821 Main (Caroline) Street and for nearly forty-four years his store was, according to a local newspaper, “regarded as one of the city’s business landmarks.”

The first mention of Jacobs’s interest in Civil War relics appears in a newspaper announcement in 1891, the same year that Cotton and Hills sold their collection. Under the heading “A Precious War Relic,” the article mentioned that Jacobs recently acquired a Bible that had been picked up from Stansbury Farm immediately following the December 1862 battle. The Bible bore an inscription inside that revealed the testament had been presented to a “W.J. Shackelford” by the Bible Aid Society of Montgomery, Alabama on June 29, 1861. The article announced that Jacobs “would gladly return this relic to the former owner, if still living, or to any member of his family who should chance to see this notice.” Apparently, Jacobs never found the owner, who was likely William J. Shackelford of the 10th Alabama Infantry. Three years later, Jacobs still had the Bible in his possession. Perhaps this acquisition spurred Jacobs’s interest in building a collection of Civil War artifacts.

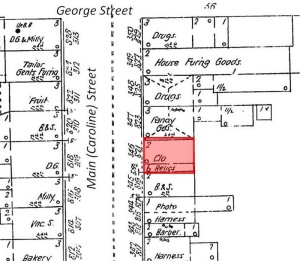

The first reference to Jacobs sharing his collection of artifacts with clients and visitors is found in a local newspaper article from 1893. This article announced another unique acquisition by Jacobs – a tree trunk with a saber through the middle of it. The saber belonged to Marshall Clay Bennett, a former member of the 9th Virginia Cavalry. According to the paper, Bennett returned to his farm in Fauquier County and stuck the saber in the fork of a tree in his front yard, where it remained for twenty years. The tree grew around the saber, yet the paper claimed “the blade can be easily drawn from the scabbard.” Someone cut the tree down and delivered the trunk to “the museum of war relics of Mr. B.H. Jacobs, on Main street.” The presence of Jacobs’s “museum” is verified by the Sanborn Fire Insurance map for 1896. Next door to his clothing business, at 819 ½ Main Street, is an area simply identified as “Relics.” This must be Jacobs’s museum, as the map shows an opening in the wall between the two addresses.

A section from the 1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance map for Fredericksburg, Va. Note the reference to relics housed next to Jacobs’s clothing store.

By 1894, Jacobs had amassed a sizeable collection. He issued a catalog that year that listed the items he owned. Three years later he issued an updated catalog, which can be downloaded here, that contains descriptions of 497 items in his collection. The artifacts included uniforms, weapons, ordnance, books, and slave receipts. Some of the item descriptions contained associations with individual soldiers.

How long Jacobs maintained his “museum” remains a little uncertain. The 1902 Sanborn map shows the space next to his clothing business as being used for “Curios,” which suggests he maintained his display into the 20th century. The 1907 insurance map, however, does not reveal a use for that area. It’s quite likely that Jacobs liquidated his collection, either no longer retaining interest in the relics or desiring their monetary value. Either way, around 1906 he sold his relics to a new collector in the Fredericksburg area.

Elmer and Blanch Agan came to Spotsylvania in 1904. Natives of New York, the couple acquired the 760-acre “Forest Hill” property near Hamilton’s Crossing. This had been the wartime plantation of Jane Hamilton Marye, wife of John L. Marye of “Brompton.” Although fire destroyed the antebellum house in 1869, the Agans purchased this historic landmark property. Elmer, it was said, took an immediate interest in the relics and artifacts that could still be found lying about the area’s battlefields. One story states that he “drove in a spring wagon all over this part of Virginia purchasing all Civil War relics that the owners would part with.” He began to purchase single pieces and collections, to include that owned by Bernard Jacobs. There is no evidence that Agan displayed his collection locally, but he instead sought a national stage upon which to exhibit his Civil War relics. In 1907, Agan packed up his collection and took it to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. From a handbill advertising Agan’s exhibit, his “Museum of Civil War Relics” was located on the expo’s midway, known as the “Warpath,” and opposite the Battle of Gettysburg Building.

The expo turned out to be a bit of a bust, as a result of low attendance. Agan returned to Spotsylvania and became the secretary of the Fredericksburg Home Brand Canning Company. Although he and his wife retained Forest Hill until 1915, they moved their residence to Maryland. Perhaps it was the distance from the battlefields or the depressing turnout at the expo, but Agan chose not to take his artifact collection with him. Instead, he entrusted the relics to the canning company’s president, Oliver M. Armstrong, who put the relics into storage.

Between Cotton, Hills, Jacobs, and Agan, relics from the local battlefields had been on display in Fredericksburg for twenty years. When Agan put his collection in storage, no such exhibition remained in the town. Some local citizens came to view theses exhibits and displays as a benefit to their community. A desire to see a museum dedicated to Fredericksburg’s Civil War history became an interest among some within the town. In 1912, an editorial appeared in the Virginia Daily Star. Entitled “War Relic Museum – Proposed Permanent Collection for Fredericksburg,” the column decried the fact that these private collections had been gathered, displayed, but always short-lived.

“Fredericksburg is growing poorer and poorer in such things, and the time will soon come when it will be impossible to make a full collection of such articles for our community. The most logical place for the preservation of articles of historical value is undoubtedly the community wherein the event occurred with which they are connected.

Can a collection of this kind be made for Fredericksburg and be placed on permanent exhibition in a building easily accessible to our citizens? We think so.

Why not have a museum in Fredericksburg?” – “War Relic Museum,” Virginia Daily Star, December 16, 1912

This plea for a permanent Civil War museum in Fredericksburg fell on deaf ears. For sixteen more years, the collection gathered by Jacobs and Agan remained hidden from view in a building behind Oliver Armstrong’s house. Not until 1929 would interest in these artifacts result in another museum to display the tangible remnants of the Fredericksburg’s Civil War history.

A follow-up post, found here, looks at the re-emergence of the Jacobs-Agan collection and the opening of the The National Battlefield Museum.

It should be noted that the first historians to look at early Civil War relic collecting, to include these Fredericksburg collections, were Stephen W. Sylvia and Michael J. O’Donnell in their wonderful 1978 book The Illustrated History of American Civil War Relics (Orange, Va.: Moss Publications).

Thanks to Paul Shevchuk, Museum Technician at Gettysburg National Military Park, for allowing me to thumb through that park’s accession and research files.

Eric J. Mink

Fascinating. Enjoying this material and looking forward to the coming installments. As we have most recently seen by the departure of the “Civil War Life Museum” locally, it appears to be a continued struggle for a dedicated Civil War museum in Fredericksburg. One would think such an entity would thrive, but there is an odd antipathy and lack of support.

Perhaps we need to expand on the concept of a museum. I have talked with several folks about the potential for a regional CW visitor center/museum where Doug Wilder once proposed a slavery museum. Both NPS visitor centers are removed from the I-95 corridor, but a public/private regional visitor center, visible to interstate travellers, could direct folks to NPS visitor centers as well as other points of interest, such as the White Oak museum, the Stafford CW park, etc. There are also numerous hotels nearby to encourage visits of more than one day. Possible partners in this endeavor could be the Museum of the Confederacy (which would like to have a Fredericksburg presence), an existing or a new local non-profit organization, and possibly local/state/national governments. The standard should be something no less impressive than the new visitor center at Gettysburg. Just a thought.